Con los pobres de la tierra | (With the poor of the earth)

Quiero yo mi suerte echar | (I want to cast my fate)

—”Guantanamera” (Cuban folk song adapted from the poetry of José Martí)

We’re not even a month in and Donald Trump is snatching innocent people from U.S. soil and illegally sending them to indefinite detention in Guantanamo Bay.

We’re going to talk about this. I really don’t want to have to talk about this.

I’d so much rather talk about the other reason that people around the world know the name “Guantanamo.”

So before things get any darker please take a moment to enjoy something truly beautiful: 75 Cubans around the world joyously performing one of the greatest anthems of human solidarity in the face of oppression ever written anywhere by anyone:

“Guantanamera” is a brilliant mash-up of several of the later works of the revolutionary poet and author José Martí. It has become one of the best-known songs in the Spanish language, first popularized by Cuban crooner Joseito Fernandez and catapulted into the international zeitgeist after Castro’s revolution to the point that there are career-defining recordings of it by both Cuban superstar Celia Cruz and American folk nerd Pete Seeger (among many, many many others).

The song’s chorus is an appreciation for the simple beauty of a country girl, the verses a passionate declamation of a revolutionary’s highest ideals. The whole thing lopes along with the kind of melody which will burrow its way into your soul by the second time you hear it through. It’s all muy Cubano, in the best possible way.

Yo sé de un pesar profundo | (I know of a deep sorrow)

Entre las penas sin nombre | (among the nameless sorrows)

“Guantanamera” is now fixed in history as an anthem of Castro’s revolution, but it is also very much one for our times; a defiant manifesto of love and human feeling. But in a truly unfortunate turn of the wheel, in the past two decades the world has come to associate the name “Guantanamo” not with its fetching guajiras,1 but with the high-security black hole of torture and misery which has been operating at the 122-year-old US naval base at Guantanamo Bay since shortly after 9/11.

Guantanamo has become synonymous with extrajudicial imprisonment and torture, a handy metonym for a place where due process (and at least nine detainees that we know of) have gone to die. The name deserves better, as do the quarter-million Guantanameros who populate the region.

Okay. Well, shit. I really don’t want to talk about this. I’m going to stall a bit.

We’ve done some music appreciation—now let’s do some history.

The ongoing American occupation of 45 square miles of Cuban soil is as almost as legally murky at this point as anything that we have done to anyone housed there. The United States is operating in hostile territory in a country which it barely even allows its own citizens to visit on the authority of a questionable agreement which the Cuban government has refused to recognize (or accept payment for) for the past 66 years—while also operating in plain violation of that lease agreement and with explicitly Congressional prohibitions from abandoning this quasi-legal claim.

There’s a lot here.

Jose Martí was an early casualty in the Cuban War of Independence, killed in battle at the age of 42 in 1895. The eventual Cuban victory in that war over Spain with the assistance of U.S. forces three years later would eventually result in Congress forcing a lease granting the American military “exclusive control and jurisdiction” of a naval base and coaling station at Guantanamo Bay not just into law but into the Cuban Constitution.2 The 1903 agreement was drawn up explicitly at the price of withdrawal of U.S. troops from every other part of Cuba, a contract which could hardly be considered “voluntary” by the basic principles of Western contract law. (The 1934 renegotiation which established the lease in perpetuity at least put it on somewhat less coercive ground.) The price was set at 2000 gold coins annually.3

After his revolution in 1959, Fidel Castro refused to accept Yankee “dirty money” for the lease—both on principle, and because the US stubbornly continued to make the rent checks out to the non-existent “Treasurer General of the Republic.” (He once showed a reporter an entire desk drawer stuffed full of them.) The Cuban government cut off the naval base’s water supply several years after the US ended diplomatic relations in 1961, and it has remained solely responsible for its own water and power since then.

Is it true that the grass grows again after rain?

Is it true that the flowers will rise up again in the Spring?

Is it true that birds will migrate home again?

Is it true that the salmon swim back up their streams?

It is true. This is true. These are all miracles.

But is it true that one day we'll leave Guantanamo Bay?

—“Is it True?”, Osama Abu Kabir (released from Guantanamo Bay on 11/3/2007)

The most infamous detention center in recent Western history opened at the Guantanamo Bay naval station exactly four months after the attacks of September 11, 2001. The indefinite detentions of purported “terrorists” captured in Afghanistan and far beyond which would come to define the facility were justified by an unprecedented order signed by George W. Bush in early November 2001. This order, ominously entitled “Detention, Treatment, and Trial of Certain Non-Citizens in the War Against Terrorism” should stand in infamy along with the Supreme Court’s shameful decision handing Bush the Presidency a year earlier. The first year of the 21st century began our long slide away from anything that could genuinely be called the rule of law down a slope which has quickly become slippery to the point of actual peril in the past few weeks.4

A total of 780 men have been held in Gitmo, and contrary to what the U.S. government would prefer that you believe nearly 9 out of 10 of them were not captured by U.S. forces on the battlefield. An estimated 86% were actually sold out by locals in exchange for bounties of $5,000—a truly life-changing amount of money in the places they were captured—and as of this extensive 2006 study by Mark Denbeaux5 of Seton Hall Law 55% of the detainees held within the first few years did not have provable ties to known threats to US national security. 22 minors were held there, and the “folks” who Barack Obama would later acknowledge that we tortured included a 14-year-old.

Guantanamo Bay has been operating in violation of any number of U.S. laws and international treaties since then—and, as of the opening of the detention center, the plain terms of the lease with Cuba—but there are also serious questions at this point about the legality of closing it.

The legal situation surrounding the naval station at Guantanamo Bay is so complicated that US law arguably doesn’t allow us to close and abandon the place even if we wanted to. Turning the land, buildings, and any excess equipment we might leave behind over to the Cubans would be in violation of the sanctions imposed by the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, which prevents the U.S. from providing “any benefit” to the Cuban government. (As detailed in this Congressional Research Service memo, there are some possible exceptions and of course it should be closed under any circumstances.)

Guantanamo Bay is only about 500 miles from US soil, but it has always seemed extra remote for Americans because it is (I think quite intentionally) in one of the only countries in the world which the US government restricts its own citizens from visiting.6 It was realistically the place under US control closest to the mainland which could maintain a black site, and here we are.

Okay. This piece has been sitting in drafts for weeks now, so let’s just say it: Donald Trump has ordered Guantanamo Bay to prepare to receive and house up to 30,000 non-citizens arrested from the US interior.

This prolonged detention would not, we were assured, be in the infamous black hole of justice in which hundreds of men were held for far too many years without due process or trial, but the lesser-known Migrant Operations Center. DHS Secretary Kristi Noem directly cribbed Bush defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s description of prior Gitmo detainees in promising that only “the worst of the worst” would be sent to Cuba.

Both promises were broken within hours of these statements. The first cohorts of immigration detainees have already arrived, and some are being housed on the detention center side.

They are also not even close to the “worst of the worst.” Thanks to outstanding reporting from rockstar independent immigration reporter Pablo Manriquez7 it is becoming apparent that the Trump administration’s desperation to find and deport members of the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua gang has reduced the profile down to “Venezuelans with tattoos.”

I’ll let you take a moment to read Pablo’s original, vitally humanizing reporting on at least two of these men (don’t miss this one especially), but it comes down to this: per the families of those profiled, these detainees have no criminal records, and no known gang affiliations. This wholly unsurprising news has since been confirmed by government documents obtained by CBS News, which is reporting as of today that in addition to the “worst of the worst” that we were promised that there are many other Venezuelans sent there for no other reason than that they are subject to final orders of removal (aka “deportation”).

MS-13 played the role of El Cuco for Trump’s first-term, but they have been substantially weakened since Trump ally Nayib Bukele has consigned thousands of suspected maras to the Salvadoran version of Guantanamo. So Tren de Aragua has been assigned the part, and the focus has shifted to Venezuelans.

It says a lot that they have already run out of Tren de Aragua members, given just how hard ICE has been working to find them. This obsession was apparently born out of some online MAGA nonsense about how TDA had “overrun” Aurora, Colorado. But of course that never happened, and you don’t even have to take the already-credible word of Aurora’s mayor on that at this point. Yahoo News reported last week that 400 ICE agents were dispatched to Denver and Aurora to spend an entire day trying to find TDA members and came up with only one person between them.

I will say this: I have worked with many asylum seekers recently who came to the US to escape TDA, and at least anecdotally they do seem capable of a kind of audacity even beyond the Central American maras.8 But there are just aren’t that many of them in the US, and holding them in the same facility as Khalid Sheik Mohammad when there is already more than enough infrastructure in the MOC is sending a very obvious dual message: to Americans as to what Trump is willing to do to enforce immigration law, and to the rest of the world as to what this administration will do to deportees.

There are, for whatever it may ultimately be worth, real potential legal challenges to all of this—at least one of which has already worked to stop the removal to Cuba of three Venezuelans in ICE custody who convinced a federal judge that they fit the profile—but for now as this all develops I will leave that to finer legal minds. For now I’m more interested in naming this moment before it passes by with all of the rest.

At more than $7 billion, the detention center at Guantanamo Bay has been the most expensive carceral project in human history. As of 2019 it was averaging approximately $13 million per detainee. Even assuming that it would be far less per person for a more standard detention camp with less security, the transportation and detention of the 30,000 people that Trump has promised would be absurdly more expensive than simply expanding the massive ICE detention centers which already exist in Texas and Louisiana, or building new ones in any number of places. It is absurdly impractical to export people to a completely different country before deporting them, and well beyond the ways in which the government is usually absurdly impractical.

But this isn’t about practicality.

This executive order explicitly slams the Overton Window on Guantanamo Bay dramatically to the hard right in a way which I don’t think that we have had enough time to begin to appreciate, and to a point which is already urgent. It is one (very bad) thing to have a black hole of due process reserved for hundreds of people of dubious complicity in acts of terror from around the world who were never convicted of a crime,9 but it is quite another (arguably far worse) thing to normalize the idea that it is a place which also houses people who have been forcibly removed from U.S. soil. For everything else that is going on right now, that is still something which is worth taking a moment to really sit with.

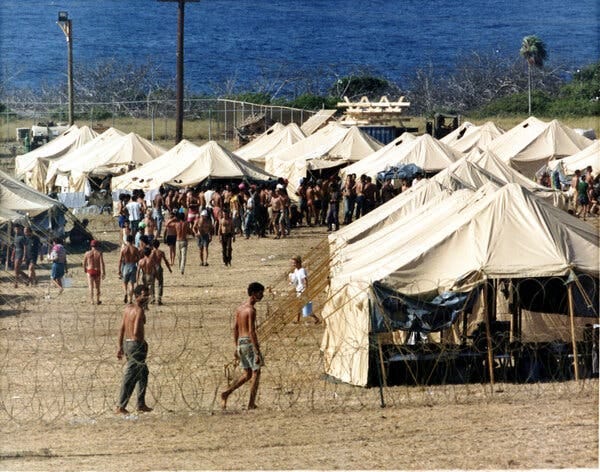

Housing 30,000 people in a single US naval base sounds like a difficult challenge—and it is—but we know that we can do it at Guantanamo Bay because Bill Clinton already did. Approximately that many people who were intercepted trying to leave Cuba by boat were detained at the Migrant Operations Center at Guantanamo, followed soon thereafter by a total of approximately 20,000 Haitians in the following years.

Clinton’s treatment of Haitian asylum seekers was a shameful (and, by his terms, successful) effort to do everything possible to keep them from reaching protection in the US. At its peak in 1995, the Migrant Operations Center had approximately 25,000 Haitians living there while Clinton bureaucrats sorted them out under the dictates of the ominously-titled Instruction 5500. These standing orders were explicitly designed to keep the residents of the MOC from being allowed to come to the United States. (From 1981-1989 only six out of more than 20,000 Haitians to pass through there were granted asylum.) The conditions at the MOC have always been bad, and two journalists held there with their children for five months in 2022 reported a hellish and unsanitary experience.

I mention this not to say that Trump’s plans for Guantanamo Bay aren’t concerning, but only that they aren’t entirely unprecedented. But what is new here is the idea of forcibly relocating tens of thousands of people from the interior of the US to somewhere other than their home countries.

—

Pete Hegseth is the first Secretary of Defense to have been deployed to Guantanamo Bay, and he is now in many ways a product of that time there.10 He has described his frustration with the facility soon after he arrived and the feeling that they were just babysitting some of the country’s most avowedly dangerous enemies with no progress toward justice. He went from Gitmo to even more frustrating deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan, watching friends disabled, killed, and traumatized for nothing that he (or I, or really anyone else) could understand.

It does seem from everything we know that Hegseth was a real shithead well before his enlistment, but without extending him too much personal sympathy I can also see how someone who had been let down that many times by an organization he had expected more from after years of dedicated service could turn out to be a bitter and potentially violent alcoholic who hates half the country.

Guantanamo made him. It will unmake us.

Guantanamo Bay has been a symbol of American hypocrisy for decades now, but it is only the most starkly visible of the many options. We already had an established history of herding one class of unpopular minorities into undesirable locations well before the Trail of Tears, and a relatively recent example of the establishment of internment camps within the US interior by executive order to punish others.

The detention center at Guantanamo Bay is famously a legal black hole, with a military tribunal not bound by anything resembling Constitutional norms or U.S. legal precendent. There’s no way that this existing reputation wasn’t part of the PR calculus here. They fully want us to know and believe that.

Venezuela has been refusing to recognize or accept deportees back for many years now. I have represented many people in similar legal limbo, mostly from Cambodia and Vietnam. Most of them were members of street gangs or otherwise caught up in bad company in their youth, and for the most part are now fully reformed and rehabilitated members of society—truly some of my favorite clients. But their criminal records are classified as super-deportable “aggravated felonies” for federal immigration purposes, and that is all the system is allowed to see.

Whether the intention is to hold people who already have removal orders—as it has apparently been as of the date that I am publishing this—or to hold people pending removal proceedings before an immigration judge—as it very well be by the time that you are reading it—I don’t think that this should be legal, and it should be stopped. From denial of counsel to involuntarily triggering bars to future immigration options which kick in when someone leaves our borders (voluntarily or otherwise), there are all kinds of potential violations of due process and basic legal and Constitutional rights in play here. But I also can’t say that it’s plainly illegal on its face to relocate immigration detainees to a military base abroad, and of course once we reach the point that there are military planes routinely shipping tens of thousands down there maybe court orders won’t matter so much anyway.

While it does seem that Venezuela has bowed to Trump’s pressure this week and begun to accept a trickle of deportation flights, there are (for very good reasons) far more deportable Venezuelans in the U.S. than Maduro is likely to ever begin to accept.11 I have no doubt that the Trump administration plans to use this to set up a challenge to the Supreme Court’s 2001 precedent in Zadavyas v. Davis, which established that no one can be detained in immigration custody for more than six months if their deportation is not “reasonably foreseeable.” And Guantanamo Bay is infamously the last place within U.S. jurisdiction where it is reasonably foreseeable that you will be released.

Okay. More words than I meant to use here, but we can do this. We’ve reached the point that I wanted to make here, the one that I haven’t been able stop thinking about for weeks now. The one you’ve most likely thought of yourself while reading this.

Once this is a normal thing to do to non-citizens, anyone could be next.

The Niemoller poem “First They Came” has become a cliche, but it is a cliche for a reason. Niemoller perfectly immortalized his times by beginning the poem with “first they came for the Communists,” and of course he knew all too well that political opponents of the Third Reich were the first people sent to concentration camps.

But the poem skips over the next and perhaps most critical piece of the normalization of the camps: the internment of “habitual criminals” and other people with serious criminal records.

The worst of the worst, if you will.

You don’t need to read the poem to know what came next. We all know that history, and there are even still a precious few among us left who can tell you about it themselves.

The U.S. already has the largest system of mass incarceration ever built, and we have consistently deported non-citizens at a level which I would consider “‘mass” for most of my lifetime. We are already far too inured to all of it.

But this—this is not a thing that we have done before, and it is not a thing that we should tolerate now. This has started with Venezuelans and “migrant crime” and “gang members,” but it will never end there because it never does. Let’s not wait for someone else to speak for us.

Cuban slang for “country girl”

"To enable the United States to maintain the independence of Cuba, and to protect the people thereof, as well as for its own defense, the Cuban Government will sell or lease to the United States the lands necessary for coaling or naval stations, at certain specified points, to be agreed upon with the President of the United States."

I haven’t had time to look into this, but multiple sources say that the US has been sending checks in the amount of $4,085 for many years. I don’t know why that amount rather than than the $47,000—which would still be a bargain!—that $2000 USD in 1903 would be worth today, but since Cuba isn’t accepting it anyway it doesn’t seem too important for present purposes.

This should not be read to suggest that the United States was a shining paragon of legal virtue until the beginning of the 21st century, but only that the combination of the nation’s highest court intervening to decide an election followed months later by the President they chose authorizing a completely unique form of extrajudicial/extraterritorial detention constituted a new and markedly low point for modern American law from which we would only continue to descend. I have to believe that we can truly restore the rule of law and ethical governance without fear or favor within my lifetime, mostly because I need to believe that to host an American legal podcast as of February 2025.

I was fortunate to have Prof. Denbeaux as my 1L contracts professor, and I thank him both for not going easy on me and for what little I still remember about the law of contracts 23 years later.

It is not illegal for US citizens to visit Cuba, but only to visit for purely touristic reasons and/or to spend money there without an approved purpose for the trip. Iran is under somewhat looser but similar sanctions about what US citizens can do there, and so far as I know North Korea is the only country in the world for which it is a crime for Americans to visit.

I’m a subscriber to Migrant Insider, and you should be too

To name one of many examples, I have a very credible account from a client of TDA corrupting a local hospital to the point that they were able to run a particularly gruesome scam during the pandemic in which they would hold the bodies of COVID victims hostage and sell them back to the families.

One of the most dire facts about this black hole of due process is that more detainees have died at Guantanamo Bay than have been convicted of any crimes by the standing military tribunal

Florida governor Ron de Santis is also an alum, and is known to have stood by to observe waterboarding of several detainees.

Many, if not most, of the deportees will have tried and failed to bring asylum claims in the US, and there is good reason to be concerned for what will happen to them as well given Venezuela’s brutal response to political dissidents. (This was one of the primary reasons for Biden’s grant and recent extension of Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelans, revoked earlier this month.)

Matt has added depth to this discussion with music, history and context. How lovely and worth fighting for.

Surprise the prison corporation setting up Guantánamo Bay for deportation has a history of human rights abuse. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/20/guantanamo-migrant-jail-akima-revealed?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other